Publications

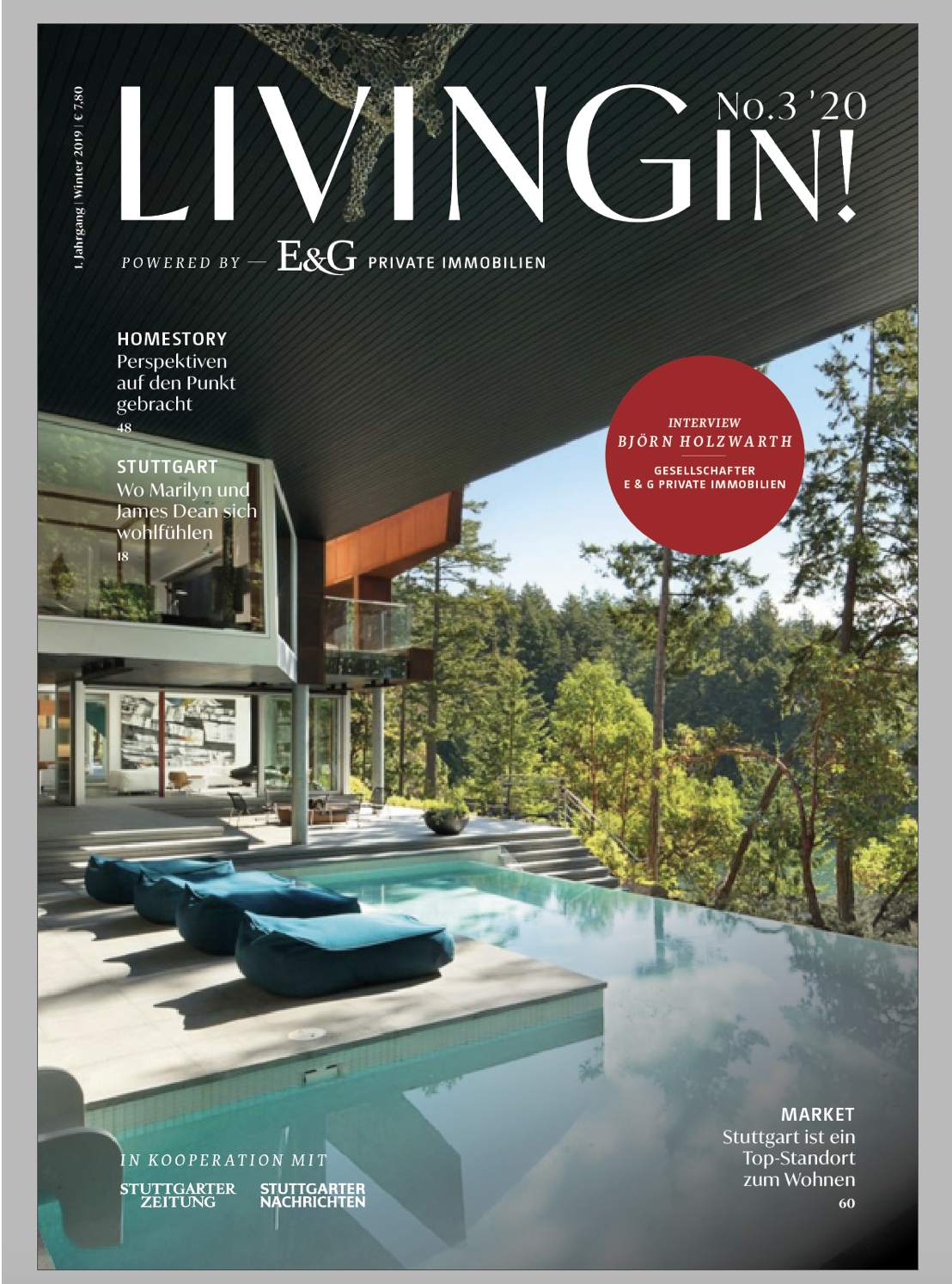

WInter 2019 cover and article of Gulf Island house in Living in! Magazine. German publication:

The Kits Beach Restauran

t and Lifeguard Facility was published in: 'Canadian Modern Architecture: A Fifty Year Retrospective -1967 to the Present' Hardback.

Kenneth Frampton, forward. Elsa Lam, ed., Graham Livesay, ed. Adele Weder, Writer. Princeton Architectural Press. 2019

The Cube House is published by Objekt International Magazine, Spring 2019

The Gulf Island House is published in Architectural Digest Mexico edition, May 2019

The Gulf Island Residence is published in The Plan, Italy May 2015

The Gulf Island Residence is published in Azure, October 2014

The Gulf Island Residence, Tofino Residence, and UBC Residence appear in Western Living September 2014 Designers of the Year Issue. See article and video, below.

The Gulf Island Residence appears in Objekt International Magazine, Netherlands, June-August 2014 issue.

The Tofino Residence appeared in International Architecture and Design Magazine Spring 2013

Article and video on WL 2014 The "Architect of the Year" Award:

http://www.westernlivingmagazine.com/2014/08/26/aa-robins-architecture-doty-2014/

http://www.westernlivingmagazine.com/2014/09/08/video-western-living-doty2/

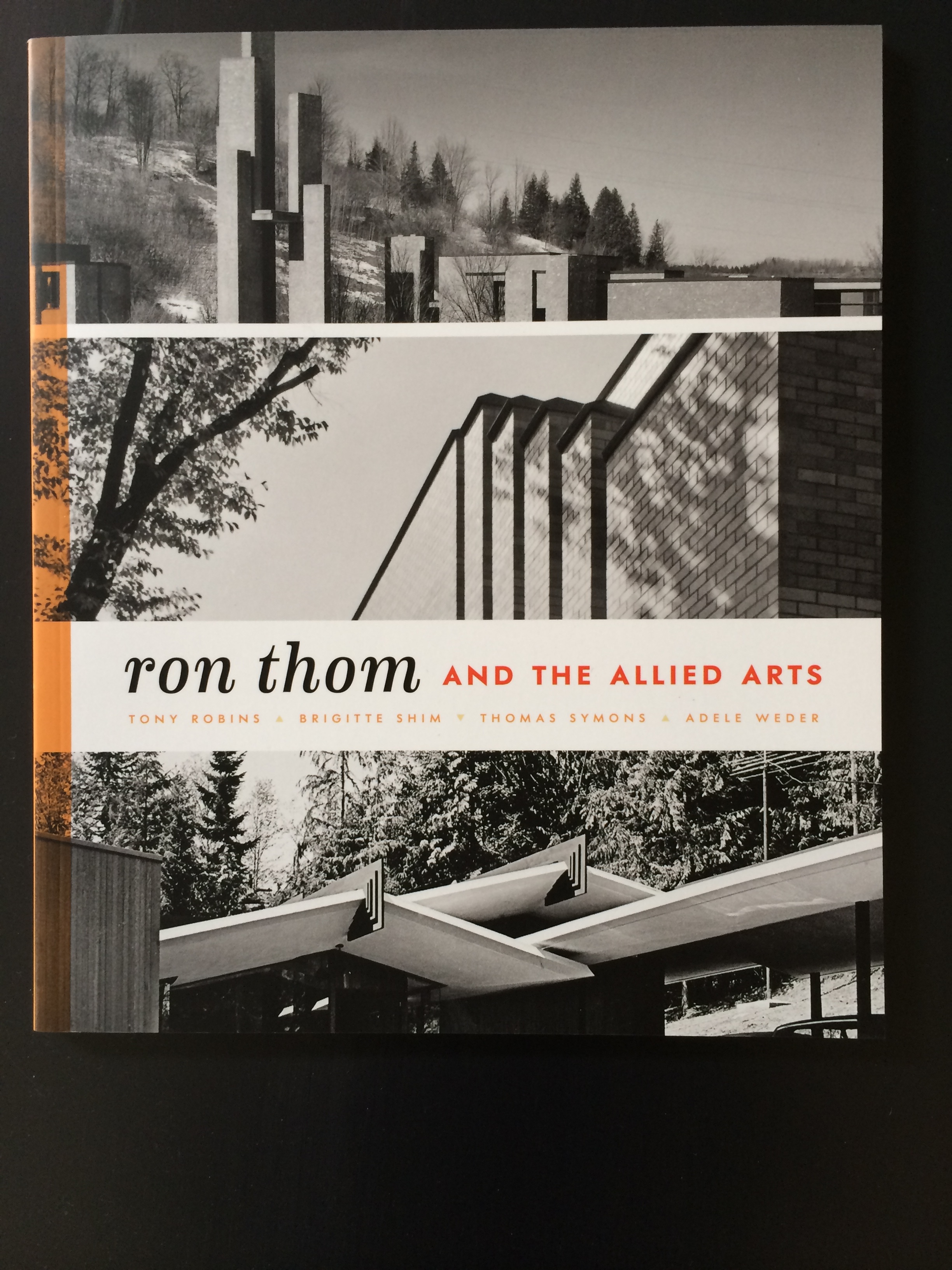

The following publication on Ron Thom formed part of an exhibition curated by Adele Weder that traveled nationally. The piece speaks to the spatial techniques Thom gleaned from Frank Lloyd Wright and made his own by contextualizing them to the West Coast.

BEYOND A FORMIDABLE SHADOW

Observations on Thom’s West Coast Spatial Mastery

There’s a discreet, shared acknowledgement surrounding Ron Thom’s architecture: a silence, followed by a nod or a headshake, accepting and forgiving the massive presence of Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright’s work was a prime resource for so many North American architects in the first half of the last century, mostly because he was brilliant, but also because his style was both uniquely American and seductively holistic in its incorporation of every visual element. Like many European movements around the turn of the century, he imbued everything with his style, from custom-designed chairs and light fixtures to cutlery and concrete blocks. For Thom, Wright served as great influence in his early years coming up to speed as an architect with no formal architectural education—remarkably, like Wright’s own self-taught career. Standing in those very large shoes, Thom joined a nationwide group of followers that included his contemporary and chief “competitor,” Arthur Erickson. It was, I believe, a grand training and a valid one. Music students compose in the style of Beethoven and Mozart to understand masterful composition, to grasp the “rules,” and only then go on to break them in a personal way. Looking at many of the world’s leading architects, one sees similar paths that springboarded them to great things. As a result, however, North America is littered with half-baked versions of Le Corbusier’s La Tourette Monastery, Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building and the like. Thom implicitly defended this approach, in his observation that “Every child learns by imitation.” It takes at least half a career to establish one’s own architecture, and most (of us) never really achieve this.

The necessary step, then, is to jump from imitation to meaningful appropriation. “Good artists copy, great artists steal” is a phrase variously attributed to Picasso, T.S. Eliot, Faulkner and Stravinsky. It describes the necessary step up to establishing a unique voice in any art form. Usually this is achieved by a ”mash up” of several influences, like fusion cuisine creating a new taste. In film, Quentin Tarantino references many actual moments from his favourite movies, considered “homage,” and clever, because the resultant montage is undeniably his own. The audience becomes part of the game too, enjoyably spotting the multiple references. For Ron Thom, the compilation was a mixture of Wright with a sprinkling of Neutra and some Schindler, along with all of their profound Japanese roots.

Ron Thom swung from letting his guard down by replicating Wright—I think here of the Carmichael House floor plan, or the truly lovely but derivative precast concrete blocks for the Boyd House fireplace—to excelling at using Wright as a starting point to something new. Where he really stands out is in appropriating spatial devices, in a way that moved on from matching Wright’s implementation of them. Although I am not a Thom scholar, I can speak to architectural space. At architecture school in England, I looked at the effect of wall mass on spatial experience, learning from my own mentor Richard Padovan, who had discovered the Dutch monk van der Laan and translated his writings on spatial insights. More recently, at the University of British Columbia School of Architecture, I have been teaching an annual studio exploring architectural space. I have catalogued twenty-six techniques, a tool-kit of ways to manipulate the spatial envelope: the walls, floor and ceiling that create space. I’d like to reveal several of Thom’s spatial techniques—both absorbed from Wright and developed further—that I believe contribute greatly to our reverence of his work.

Wright’s penchant for spatial “compression and expansion” was a clear influence on Thom. The idea is to lower the ceiling of, for example, an entry space in order to reinforce the delight of higher volumes elsewhere. In much the same way, a song does not begin with the chorus, but acclimatises the audience to a more minimal sound, thus creating a far greater effect when the full choir kicks in. Wright scaled spaces to his own stature in the first place, resulting in his standard ceiling height of only 7’-6”. When downsizing that, he succeeded in a really apparent compression of space. My hair virtually brushed the ceiling of the entry area of Wright’s Robie House, and I intuitively ducked entering his church lobby in Kansas City. Thom uses this effectively in the Dodek House. The blunt, low and confined entry room demands an axial twist as one perceives the relief of the living room to the left and its intrigue of spatial height variations and textures beyond, drawing one in as the light begins to reveal the space above and beyond, out of the shadow.

A second technique is to play “dark against light,” often introducing daylight into a room in an unusual way to enhance this contrast. It ties contextually to a forest experience (Case and Boyd House) and in some cases (Dodek and Works/Baker House) to the garden immediately outside: the Japanese influenced play of light on leaves, of one’s constant viewing of patches of strong light piercing the canopy and dark low spots one has to work at to understand. Wright—and then Thom—introduced light selectively at the ceiling level as long thin window bands, bringing one’s eye upward to note the ceiling plane. Otherwise, a ceiling normally more or less disappears above one’s vision. Thom had no fear of dark corners— all the better for the drama of the overall volume, providing formidable shadows of the real kind. Some homeowners have felt compelled to add windows or incorporate a ridge skylight; to quote one occupant: “dark and moody is not so easy to live with!” My first thought was that these dark interior patches had been a mistake: an inexperienced architect not getting it right! That was naïve, I later realized; what happens when there are dark corners is that one’s eyes adjust to the space gradually. On this principal, Sigurd Lewerentz designed an entire brick church in Sweden, a dimly lit but superb structure that allows one’s experience of the space to fill in as the eye slowly begins to put the pieces together. One sequentially sees things not immediately apparent, and I found this ploy a delightful experience in the Dodek House. Wide roof overhangs limit the bleaching of the space through all of that glass, and the brick fireplace sits there in the dim light like an old silent man in a chair waiting for you to notice him.

This leads to a third technique: “spatial ambiguity.” Here, Ron Thom began to move away from Wright’s hold. He sometimes combined the high windows with beams flying though the spaces so that there is a whole other volume of space above them, a lofty and curious, spatially ambiguous, other world up there. The unclear definition of the room, such as the Copp House living Room, immediately makes the room feel more spacious than dimensions might attest. The often non-palatial homes feel expansive. No single wall seems to define the room, and one is left wondering how far the space actually stretches beyond what is immediately visible, as one looks diagonally up through layers of spatial events. Suddenly there is light coming in unexpectedly, way up in a corner, to ensure the height and drama is truly felt.

Ron Thom’s fourth spatial gesture was to incorporate surreally large-scale fireplaces, probably inspired straight from Wright. But unlike his mentor, Thom contrasted the massive hearths with a generally ethereal lightness throughout the rest of the building. This touches a few spatial tools: “heavy against light”, “tactility” and “materiality.” The wood-stud walls, cedar clad both inside and out, the floor-to-ceiling single-glazed windows with butted glass and the thin roof all add to the sense of ephemerality and the delightfully contrasting lack of weight. Cedar is feather-light. One can do harm to it with a fingernail, and its presence everywhere, on ceilings and cabinetry as well as walls, uplifts the room with its fragility: a diminution of room mass against the powerful brick hearth. Here Thom breaks into his stride, managing to refer uniquely to the temporality of the West Coast, from the disappearing relics of the First Nations’ buildings and totems, the beautiful rotting trunks within our distant virgin forests, and to the superficiality of Western presence in these regions. The massive fireplaces bring gravitas and a welcome harkening to medieval times, the weight —all that history and ancient building—of Europe, to our own thin new city. Doubly, they harken back to campfires of thousands of years of habitation before European contact. They are simply perfect for Vancouver, a contextual tour de force in part because of our subconscious desire to fill that void. They ground the building and, interestingly, they literally provide a seismic, structural grounding too, in our earthquake-prone province.

The most powerful example of this is in the 1957 Carmichael House. It stands as if the whole room is subservient to its power. In 1962 Thom did it again in the Forrest House, taking up the whole wall with stone, in a more 1960s fashion, refining the look into a whole new generation of massive fireplaces. It literally becomes the room. The sofas built in along the edges are reminiscent of the stone ledges within old European precedents, where one actually sits inside the hearth. Another moment of delight for me was experiencing, within the Copp House, “the air of immobility that precedes decay” to borrow a phrase from Martin Amis. The fireplace stands defiantly against the slow demise of its surroundings, the patina of water-stained cedar, leaky single-paned windows, tattered leather chairs, and disintegrating drapes.

A related spatial generator is the “effect of the construction process” on the space. The interior character of Peter Zumthor’s Bruder Klaus Field Chapel, for instance, is defined by how it was built: stacking twelve metre tall logs into a pyramid, pouring concrete on the outside, and setting fire to the timbers. Its blackened, inverted lines of the resultant interior tell of its construction history and the labour that went into it. Ron Thom’s enormous brick fireplaces tell of the laying of each brick. We’ve seen bare brick walls before, but never stacked so monumentally inside Vancouver living rooms. There’s a presence, in those spaces, of this labour and care and human interaction with the material. And there was probably time, before TV and the internet, to sit in one’s easy chair and appreciate that.

Ron Thom’s most unique achievement is perhaps, then, his positioning of these directly inspired spatial moves into an Architecture that suits—and is about—its context: the West Coast landscape. He had significantly stepped out on his own in thinking of space as a contextual referent. The Case House exemplifies this well. Wright’s most relevant site-contextual work is the remarkable Kaufmann Residence, Fallingwater, where he used circulation and the curving paths and stairs to hug and reveal the rocky ravine. But when it came to the main interior spaces, he designed them as flat, rectilinear volumes in contrast to the land. The main cantilevered space gains power from one’s sense of hovering over a natural riverbed to the sound of… falling water. In the 1965 Case House, Thom instead wrapped his interior spaces over the West Vancouver bedrock, giving one a sense of a forest walk, albeit from kitchen to dining room. The Case House spaces literally cascade down and over the actual granite rock face. Though in fact precisely determined by the Wright-influenced “diamond grid” plan, the seemingly haphazard angling of the ceiling and walls convey a movement that reflects the flow of the land as one might negotiate rocky terrain and cedar canopy. Where they fall apart is only when he visually refers back to Wright’s geometries. We see moments when he has lapsed into mere replication—a hexagon here or there—but then has taken off again with unique confinements and openings. I became a Ron Thom fan in that house, and sought out and rooted for the specific moments where he had broken from his mentor.

The Case House shows a freeing of roof form, again reflecting the forest canopy, but a more sophisticated development is the entire roof spectacle of the Forrest House. “Angled or curved against straight” is a spatial play most often implemented on plan, such as by Le Corbusier and Robert Venturi, and dramatically in the Crawford Residence by Morphosis. Highlighting a deviation from the orthogonal is most effectively achieved by Thom, however, in three dimensions: the swooping angles of roofline in the Forrest House. They not only create a sculptural building but directly generate the volume of the interior spaces in the modernist tradition, and—unusual for Thom—in white too! The roof is constructed mostly of a single folding plane defining both exterior and interior, contrasted against the flat surface of the ground. Three of its interlocking roofs read as a flock of Canada geese zooming away. (Sadly, their original “bodies,” the vertical deco beam elements affixed along the ridges, have disappeared in recent renovations, and more depressing still is the prospect of potential demolition of this historically priceless home). These birds in flight were another of Thom’s blatant—though maybe not conscious—contextual references to nature.

It is through all of these extraordinary spaces, then, that we see Ron Thom as a man inspired, spellbound, and driven for a long time by persuasive influences. We see how he rode those ideas to new ground in Vancouver, however, by taking existent spatial ideas and fusing them spectacularly with the contextual opportunities of the West Coast, thereby making them his own. Whilst still living in Vancouver, Thom moved to larger work, and began all over again to grapple the Wright’s impact on him. It permeated his first scheme for the Massey College competition. The jury, which included architects Geoff Massey and Hart Massey, informed him that he could move on to Round Two but needed to drop that stifling Imperial-Hotel vocabulary. It was, implicitly, a plea for Thom to allow his own immense but latent skills to flourish. He did, and they did, and we should thank the Masseys for helping Thom to establish his rightful place in history. At Massey College, with a unique and fresh design, he had utilized many of the spatial tools gleaned from those Vancouver house experiments, but finally moved beyond his master’s formidable shadow

* From Shadbolt, D. (1995) “Ron Thom.” Douglas McIntyre. Vancouver